Pediatric asthma treatment is essential, especially for those under five years old, to prevent its development into the chronic stage.

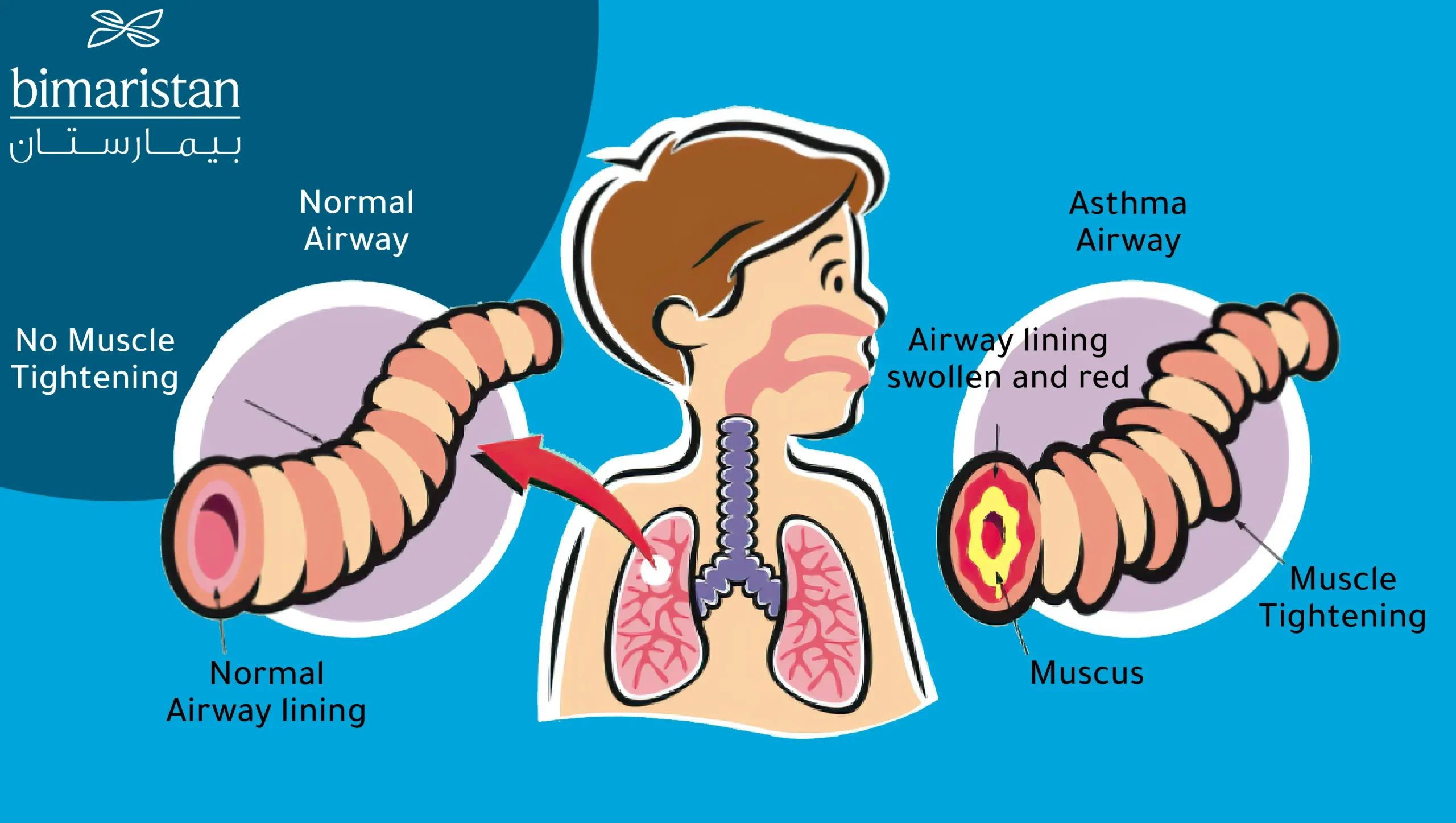

Asthma is a chronic inflammatory condition that affects children’s airways. Symptoms of asthma in children typically manifest as a persistent cough followed by wheezing (a whistling sound), especially at night or in the early morning. In this case, the child can be treated with bronchodilators. When asthma appears later, it is often familial or allergic in origin (related to inhaling allergens such as pollen), and Pediatric asthma treatment becomes lengthy and challenging.

These episodes usually accompany widespread and fluctuating airway obstruction that can spontaneously improve or be treated. Additionally, this inflammation is associated with increased bronchial reactivity to various triggers, including smoke, exertion, cold and dry air.

What is pediatric asthma treatment?

The symptoms of asthma in children can range from mild, infrequent attacks to severe, frequent attacks that require immediate emergency treatment. Therefore, based on the child’s medical history and the severity and frequency of the attacks, the doctor can develop a plan for pediatric asthma treatment. This plan includes the timing and method of administering the appropriate medication to the patient.

Many asthma medications for pediatrics contain steroids that have numerous side effects. The most important effects are bone problems, delayed growth, possible eye problems, and the body’s reduced production of natural steroids. Pediatric asthma step-up therapy includes:

Pediatric asthma treatment by avoiding triggers

It is necessary to avoid asthma triggers, which are the leading cause of asthma attacks in children, such as allergens, irritants, and sudden weather changes. Skin allergy tests can be performed to identify the cause accurately, and immunotherapy can be considered if it is not detected.

Many diseases are associated with asthma and increase the severity of attacks, such as sinusitis, as well as gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD), which is often seen in asthma patients and contributes to increased attack severity through inhaling acidic stomach contents and bronchoconstriction, especially if symptoms are present during eating or lying down.

Fortunately, no link has been proven between asthma and an increased risk of bronchial cancer, and there is no need for bronchoscopy to diagnose asthma in children.

Pediatric asthma medications

Inhalation therapy is the most crucial medication for treating bronchial sensitivity and respiratory distress in children because it requires less cooperation from the child. It also helps deliver the medicine deep into the airways, thereby reducing the accumulation of the medication on the oral mucosa, decreasing systemic absorption, and minimizing its side effects.

Two treatment approaches for pediatric asthma treatment are short-acting and long-acting. The need for long-acting treatment depends on the daytime and nighttime clinical symptoms and lung function. Among the medications used for pediatric asthma treatment are:

Pediatric asthma treatment by sympathomimetic medications

There are two types of these medications, but the most important are short-acting drugs such as salbutamol (Ventolin inhaler), which are used for emergency relief during acute attacks and for preventing exercise-induced bronchospasm. They work by relaxing the smooth muscles of the airways by stimulating their beta receptors, reducing blood vessel permeability and thus reducing edema. They also improve ciliary function in mucus clearance.

We resort to adding other medications in cases of insufficient control, such as when using more than one inhaler per month (about 200 puffs). It’s worth mentioning that there is another form of salbutamol called Ventolin syrup for children.

The second type of these medications is long-acting, such as salmeterol and formoterol. They should not be used during acute attacks or on their own unless combined with corticosteroids, in which case they can be used for treating chronic asthma. They are suitable for nighttime pediatric asthma treatment because their effects last at least 12 hours or for those who frequently use short-acting bronchodilators to prevent exercise-induced bronchoconstriction.

pediatric asthma management by anticholinergic medications

Like bronchodilator medications, there are both long- and short-acting anticholinergic medications. If treatment with long-acting bronchodilators fails, anticholinergic medications such as tiotropium can be used inhaled with corticosteroids instead.

Short-acting anticholinergic medications such as ipratropium bromide can also be used with salbutamol to treat acute attacks. This medication is typically used to treat chronic bronchitis and pulmonary emphysema.

Asthma controller medications pediatrics (Corticosteroid)

This group of medications is considered fundamental in treating respiratory distress in children at home. Delayed use of corticosteroids leads to a reduced clinical response to treatment. However, long-term use can lead to significant side effects, including bone density reduction and growth inhibition in children. To avoid these effects, corticosteroid medications are administered via inhalation, considered the least harmful form of the medication.

The goal of corticosteroids for pediatric asthma treatment is to reduce airway edema. Examples include Fluticasone, Budesonide, Mometasone, Beclometasone, and Ciclesonide.

For acute asthma exacerbation treatment pediatrics, systemic corticosteroids (oral or intravenous) are given for short periods to expedite symptom relief and prevent recurrence. As for chronic pediatric asthma treatment, corticosteroids are inhaled once or twice a day. Starting with high doses and then tapering them down as the symptoms are controlled reduces the need for emergency treatment with short-acting beta-agonists or prednisone. Therefore, the steroid-containing inhaler is considered a preventive asthma inhaler.

Leukotriene Modifiers in pediatric bronchospasm treatment

They are anti-inflammatory mediators that cause excessive mucus secretion, mucosal edema, and bronchoconstriction in the respiratory tract.

Montelukast (as chewable tablets for children) and leukotriene receptor antagonists prevent exercise-induced bronchoconstriction post-aspirin ingestion reactions and reduce the need for inhaled bronchodilators. They can be initiated for pediatric asthma treatment as young as two years old, significantly aiding in relieving respiratory distress in children while sleeping.

Pediatric Asthma Treatment by Cromolyn Sodium

It is a non-steroidal anti-inflammatory and mast cell stabilizer primarily used to treat allergies in children, inhibiting both the early and late phases of allergic asthma. It also has the potential to alleviate exercise-induced bronchospasm, serving as an alternative to salbutamol if side effects like tremors and palpitations occur.

This medication is administered through inhalation approximately three times a day, but it is less effective than corticosteroids and leukotriene modifiers in childhood asthma treatment.

Pediatric asthma Treatment by theophylline

Rarely used in childhood asthma treatment due to its narrow therapeutic index and the risk of gastric reflux through its relaxing effect on the lower esophageal sphincter in infants. It is used for acute severe asthma treatment in pediatrics. Still, caution is required when used with medications that increase serum levels, such as macrolides and cimetidine.

Using the Asthma Inhaler for Children

It is essential to know how to use an asthma inhaler in children to obtain the full benefit of the medication in the inhaler. Asthma inhalers for children can be used with a metered-dose inhaler.

Using the inhaler for children with breathing difficulties in the traditional way can be difficult for most children. Therefore, we must use accessories attached to the metered-dose inhaler device to facilitate this process. Some of these devices include:

- A spacer with a mask; The mask should cover the mouth and nose completely. We then administer the medication dose, but the mask should be kept on the child’s face for about 20-30 seconds to ensure the child inhales a sufficient dose from the inhaler (another dose can be given to the child based on the child’s condition and the supervising doctor’s recommendations).

- The nebulizer; Commonly used in children, especially those under five, converts medication into a fine mist that the child can inhale through a face mask.

- The dry powder inhaler; Permits the delivery of medication as a dry powder to the deeper parts of the lungs, unlike other inhalation devices. This device is a suitable option for older children and adolescents.

Home-based pediatric asthma treatment

There should be a written care plan for pediatric asthma treatment at home in case of asthma attacks. It should also provide parents with ample information on early symptoms that may indicate an impending asthma attack (coughing, shortness of breath, wheezing) and how to manage them promptly.

Fast-acting bronchodilators like salbutamol should be administered to children through a nebulizer every 20 minutes for an hour during an asthma crisis. If symptoms improve, doses can be spaced out, while if there’s no improvement, prednisone should by given at a dose of 1-2 mg/kg/day for 3-10 days alongside salbutamol.

If there is still no improvement, seeking immediate medical attention is advised.

For infants experiencing respiratory distress at home, bronchodilators like albuterol can be used. If symptoms worsen and do not improve, transferring the child to a hospital where they can receive systemic corticosteroids such as prednisone (intravenously or orally) becomes necessary.

Hospital-based pediatric asthma treatment

If the child does not respond to home-based treatment within an hour or if the child’s oxygen drops below 92%, hospital treatment is required. Continuous oxygen and frequent or continuous salbutamol alongside ipratropium bromide are administered.

In the case of corticosteroids, they are not only administered through inhalation but also intravenously. Thus, prednisone at a dose of 1 mg/kg every 6 hours for 48 hours is given, then the dose is gradually reduced to 1-2 mg/kg/day, with the maximum dose being around 60 mg/day.

Some children may require mechanical ventilation and intubation if they do not respond to previous treatment while still experiencing respiratory distress.

Early prevention in children with recurrent respiratory distress and wheezing (audible wheezing sound) through anti-inflammatory drugs or systemic corticosteroids plays a crucial role in Pediatric asthma treatment to prevent its progression toward chronic asthma.

Sources:

- American College of Allergy, Asthma and Immunology

- WebMD

- Johns Hopkins Medicine