Pyloric stenosis is a gastrointestinal condition that primarily affects newborns. It is relatively rare, impacting 1–3.5 out of every 10,000 newborns, and it is almost exclusively observed in children. In this article, we will discuss the key approaches to pyloric stenosis treatment and diagnosis, emphasizing that early detection plays a vital role in effective management.

?What is pyloric stenosis

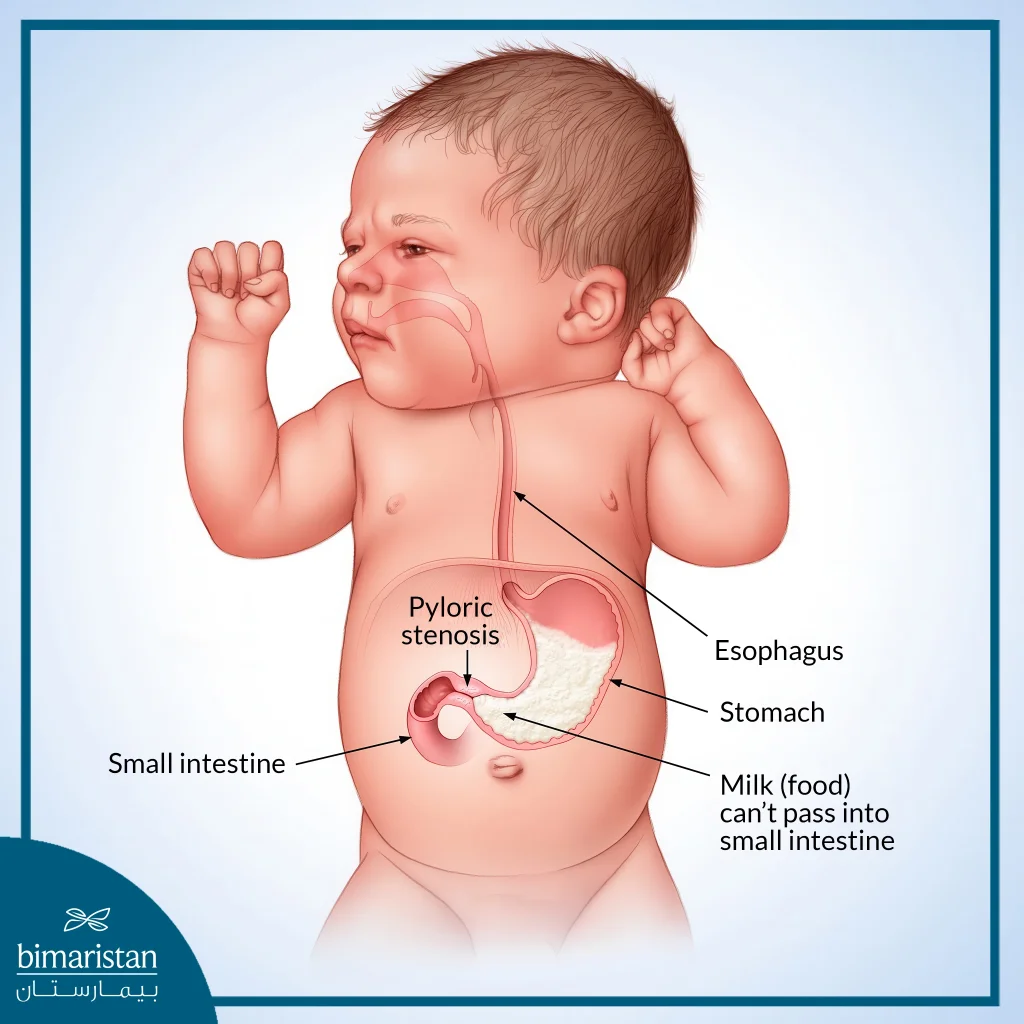

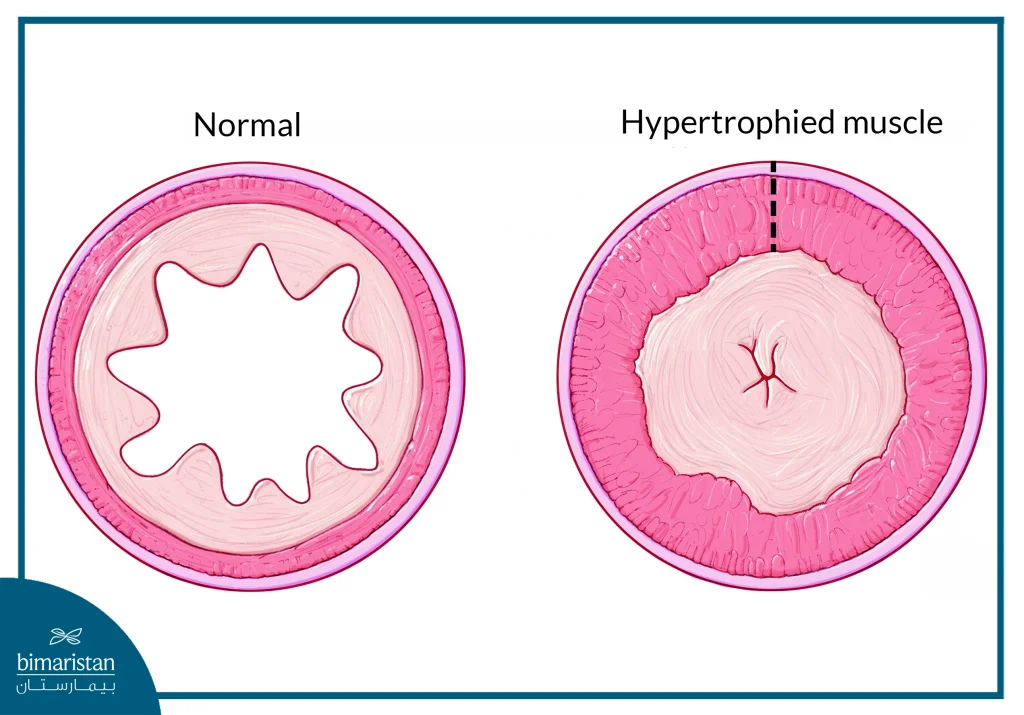

The pylorus is the part of the stomach that connects it to the beginning of the small intestine (duodenum), and it plays an essential role as a valve that allows partially digested food, ready to pass into the duodenum, to pass through gradually. Hypertrophic Pyloric Stenosis is a condition in which a narrowing of the pylorus occurs. The pylorus is made up of muscle tissue and acts as a sphincter at the end of the stomach.

Normally, the pylorus closes when the stomach digests food and liquids, and then relaxes to allow them to pass into the duodenum. However, when pyloric stenosis occurs, the pyloric muscle thickens, and this passage becomes narrow, allowing little digested food to pass. This leads to food being trapped in the stomach.

Pyloric stenosis in adults

Adult pyloric stenosis is extremely rare, and it is categorized into three types:

- Idiopathic hypertrophic pyloric stenosis (primary) is classified into two types: the first type is asymptomatic, meaning it does not cause any discomfort or symptoms, and the other one is symptomatic, often leading to gastritis or peptic ulcer.

- Secondary hypertrophic pyloric stenosis: Most common, begins in adulthood but is secondary to diseases of the upper gastrointestinal tract such as duodenal ulcers, tumors, hiatal hernia, gastric ulcers, or inflammatory diseases, and can be identified from the history of gastrointestinal diseases.

- Late-stage hypertrophic pyloric stenosis due to persistent infantile stenosis: It is easy to diagnose, going back to the medical history.

Causes and risk factors of pyloric stenosis

The exact cause of pyloric stenosis is not yet fully understood, but genetics and environmental factors are known to play a significant role in its development. Risk factors of pyloric stenosis include:

- Family history

- Firstborn (Maiden) Children

- Male Infants

- White race

- Maternal Smoking

Symptoms of pyloric stenosis

Symptoms typically begin to appear between 3 and 6 weeks of age. Affected infants continue to feed but begin showing noticeable symptoms, which include:

- Infant Projectile Vomiting After Feeding: A key symptom of pyloric stenosis is forceful, non-biliary vomiting that occurs shortly after feeding. Known as infant projectile vomiting, this condition is characterized by vigorous ejection of milk.

- Dehydration: Signs include noticeable lethargy, reduced frequency of wet diapers, sunken fontanels, dry mucous membranes, and crying with little to no tears.

- Visible Belly Ripples with Sausage-like Appearance: Abdominal ripples become noticeable in the baby’s belly after feeding and before vomiting, resembling a sausage shape

- Jaundice in Infants: A noticeable yellow discoloration of the skin and the sclera (the white part of the eyes)

- Persistent Hunger

- Infant Weight Loss

- Abdominal pain

- Antibiotics administered to newborns or mothers late in pregnancy

- Alternative feeding methods

Diagnosis of pyloric stenosis

Pyloric stenosis can be diagnosed through various reliable methods.In fact, an earlier diagnosis leads to a better prognosis. Timely intervention significantly improves outcomes and ensures effective pyloric stenosis treatment.

- Physical examination: involves detecting a small olive-shaped mass in the upper right quadrant of the abdomen. This hardened pylorus moves from left to right as it attempts to push food through.

- Ultrasound diagnosis: This non-invasive imaging technique provides a clear view of the enlarged pyloric muscle, making it a reliable diagnostic tool.

- Barium X-ray for Upper Gastrointestinal Tract: When other diagnostic methods fail to yield results, a barium scan is used to examine the gastrointestinal tract for abnormalities indicative of pyloric stenosis.

- Endoscopic examination of the upper gastrointestinal tract: We use this method when diagnostic results from previous methods fail to give results or when the infant presents with atypical clinical symptoms.

Pyloric stenosis treatment

Surgical intervention remains the definitive and primary method for effective pyloric stenosis treatment. The majority of pyloric stenosis surgeries are highly successful, providing immediate relief from the condition and significantly reducing or completely stopping vomiting after feeding. This surgical intervention is not limited to infants. It is also performed as an effective pyloric stenosis treatment in adults. In this article, we will discuss the surgical process in detail, along with the essential preparations required before surgery and the necessary post-operative care to ensure definitive pyloric stenosis treatment.

Before pyloric stenosis treatment surgery

Infants with pyloric stenosis frequently experience dehydration due to severe and persistent vomiting, resulting in an imbalance of salts and electrolytes. Effective pyloric stenosis treatment involves prompt dehydration correction, typically achieved through intravenous fluids to restore electrolyte and salt balance. Surgery is not performed until the infant’s blood test results indicate normal levels. Additionally, feeding breast milk or formula is prohibited six hours prior to the operation to minimize the risk of vomiting and aspiration during anesthesia. In some cases, a nasogastric tube may be required to empty the stomach contents before surgery, ensuring a safer procedure, smoother recovery, and achieving successful pyloric stenosis treatment.

Surgical procedure of pyloric stenosis treatment

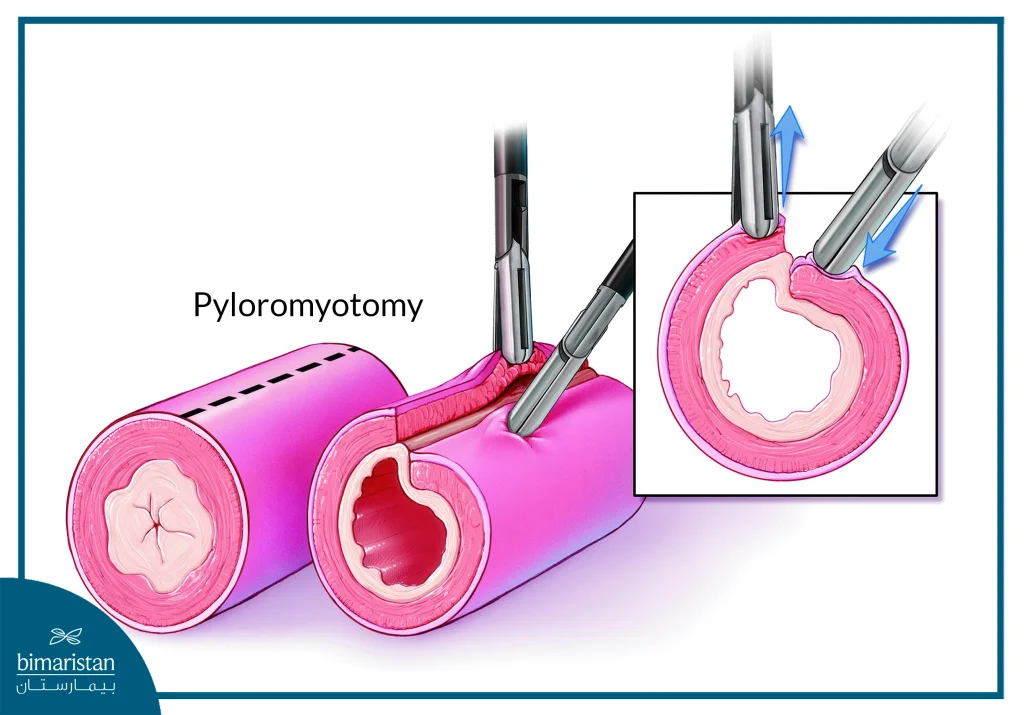

The child undergoes the procedure under general anesthesia, ensuring a pain-free experience, and the surgery typically takes less than an hour. This method of pyloric stenosis treatment is known as pyloromyotomy or Ramstedt’s operation, where the thickened pylorus muscle is carefully cut to create an opening. While the pyloric muscle retains its function, this newly created gap allows milk and food to pass into the intestines for proper digestion and absorption. The stomach lining may slightly protrude into the opening. However, it poses no risk of leakage.

Pyloromyotomy can be performed using a laparoscopic approach, which involves three small incisions in the abdomen, one for a camera and two for surgical tools. These incisions are closed with dissolvable stitches and skin glue, offering a shorter recovery period. Alternatively, open surgery may be used, involving a larger incision and a longer recovery duration.

After pyloric stenosis treatment surgery

Following pyloric stenosis treatment through pyloromyotomy, the child is returned to the ward for monitoring until their condition improves. Painkillers and intravenous fluids are administered to support the full recovery of the stomach and intestines. Approximately six hours after surgery, the child can be fed milk in controlled amounts and concentrations, based on child’s tolerance and the health provider’s instructions, especially in the case of formula milk. Breast milk can be offered from a bottle during initial feedings.

At home, the child may experience some abdominal discomfort, so painkillers are recommended for at least three days after the surgery. Loose clothing is advised to minimize irritation and reduce pain. The surgical sutures require no removal as they resolve on their own. Parents should ensure that the operation site remains dry and clean for at least two days after the surgery to support healing and should take extra care during child’s baths. A follow-up visit to the doctor is necessary within 7-10 days, or sooner if parents notice any unusual signs. Some of these signs include:

- Increased abdominal pain

- Bloated or enlarged stomach

- Decreased diaper wetting

- Recurrence of frequent vomiting

- Redness, swelling, or discharge at the surgical site

Pyloric stenosis is a rare gastrointestinal disorder that primarily affects newborns. The real causes of this disease are not known yet. The condition is identifiable through its distinguishable early signs and symptoms, including projectile vomiting, dehydration, and weight loss, making it crucial to instantly consult a healthcare provider for diagnosis. Early detection of its signs plays a vital role in managing and addressing the condition effectively. Treatment primarily involves surgical intervention with pyloromyotomy surgery to restore normal digestive function.

Sources: