Congenital heart defects in children are among the most common cardiac health issues in childhood, ranging from mild cases that often go unnoticed to severe conditions requiring urgent medical care. Since a child’s heart plays a crucial role in their growth and development, identifying abnormalities early can significantly impact their quality of life and long-term well-being.

Approximately 1 in 100 children (1%) are born with a congenital heart defect, making it the most common congenital condition. Each year, more than 1.35 million new cases of pediatric congenital heart defects are diagnosed globally. Fortunately, advancements in surgical procedures and treatment methods have enabled over 85% of children with congenital heart defects to reach adulthood with a normal or near-normal life.

What are congenital heart defects in children?

Congenital heart defects in children refer to structural abnormalities in the heart that are present from birth. These defects arise when the fetal heart fails to develop properly during pregnancy, making congenital heart defects the most common birth defects. Such conditions can impact the heart’s ability to pump blood effectively, causing irregular blood flow, whether slowed, misdirected, or obstructed entirely.

Various types of congenital heart defects may affect one part of the heart or multiple areas. Their severity ranges from minor issues requiring no treatment to life-threatening conditions demanding urgent medical intervention from birth. More severe cases are classified as critical congenital heart disease, while milder congenital heart defects may not show symptoms until later in childhood or even adulthood.

The difference between simple and complex defects

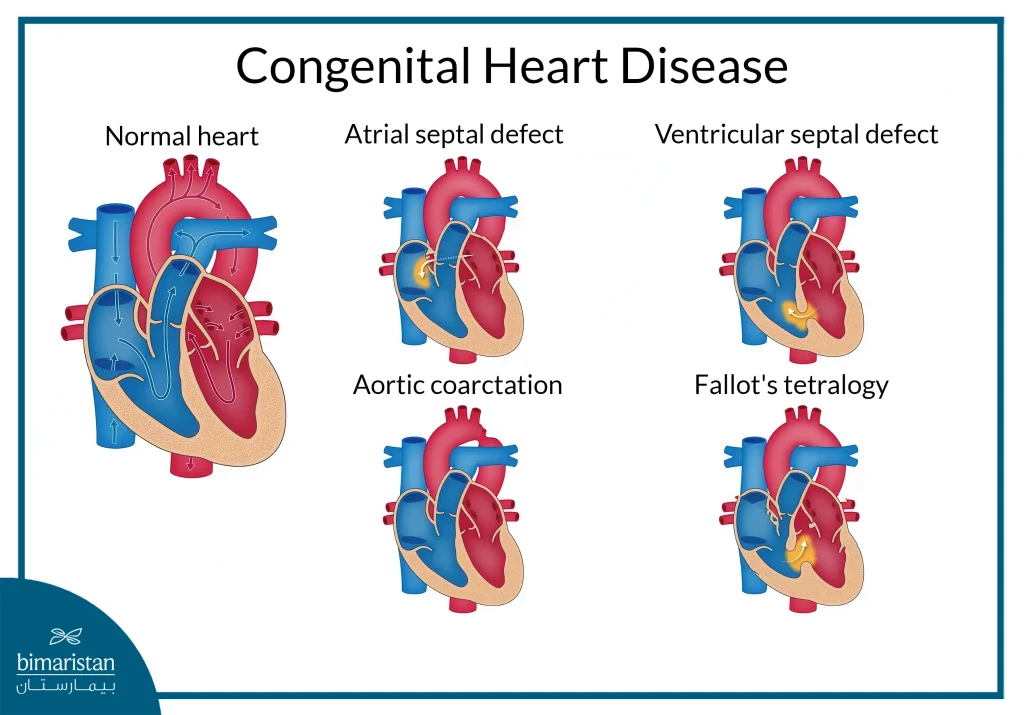

Congenital heart defects in children can vary in severity, with some minor defects potentially resolving on their own without requiring surgical intervention. These defects cause oxygen-rich blood, meant for circulation throughout the body, to flow back into the lungs, increasing pressure and straining lung function. In many cases, children with minor defects experience no noticeable symptoms. Common examples include atrial septal defect, ventricular septal defect, and patent ductus arteriosus.

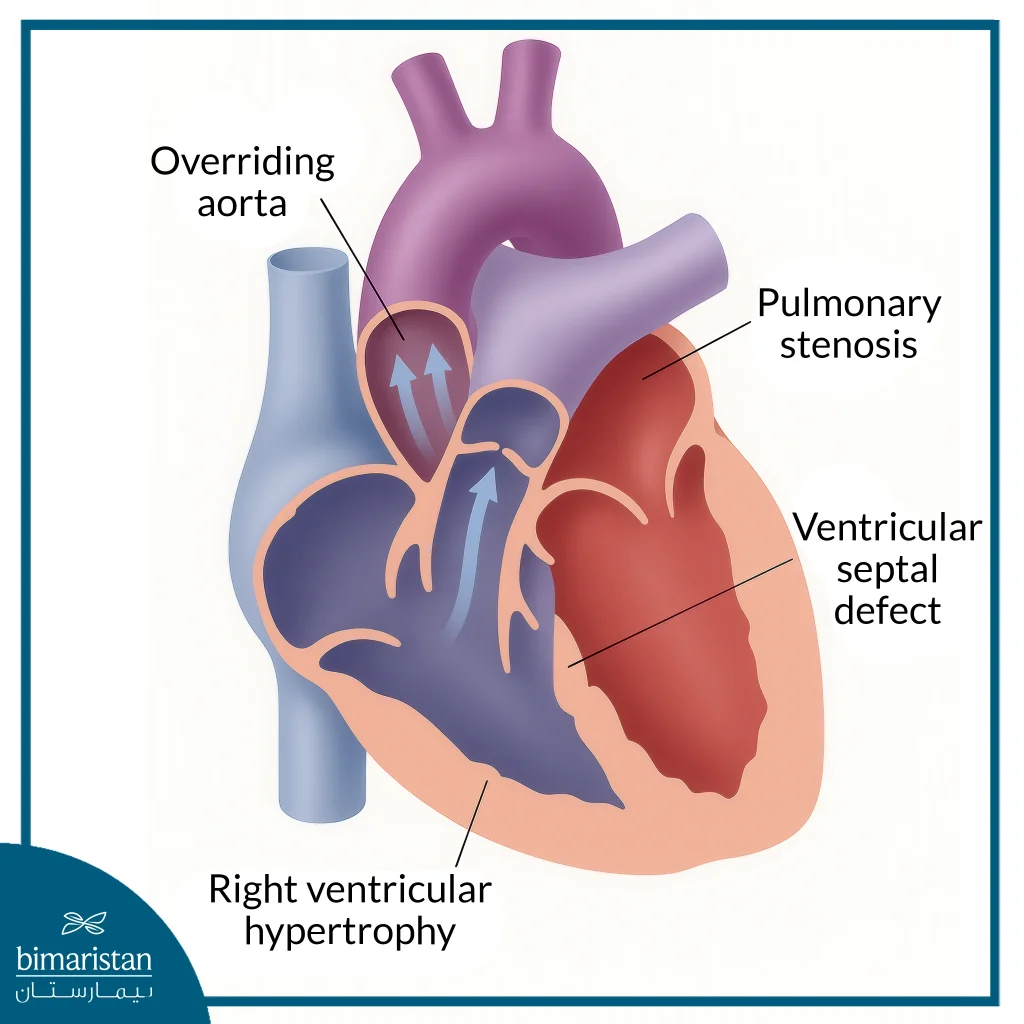

On the other hand, complex and critical congenital heart defects can present life-threatening complications that demand immediate medical attention. In these cases, blood reaches the body before being adequately oxygenated, resulting in hypoxia. Children with such defects often present with a bluish tint (cyanosis). One of the most critical heart conditions is tetralogy of Fallot, which necessitates surgical treatment within the first year of life for affected infants.

What causes congenital heart defects in children?

Certain factors can increase the risk of developing congenital heart defects in children:

- Down syndrome, a genetic disorder that affects a child’s physical development and cognitive abilities

- Maternal infections during pregnancy, such as rubella

- Use of certain medications during pregnancy, including statins and specific acne treatments

- Exposure to harmful substances, such as smoking or alcohol consumption during pregnancy

- Poorly managed type 1 or type 2 diabetes in the mother

- Chromosomal abnormalities, which may interfere with normal development, can sometimes be passed down genetically

The fetal heart begins forming and beating during the first six weeks of pregnancy. The major blood vessels responsible for carrying blood to and from the heart start developing at this critical stage. At this stage of fetal development, congenital heart defects may begin to form. Despite ongoing research, the exact cause of most defects remains unknown.

Common types of congenital heart defects in children

Congenital heart defects in children include a variety of structural heart abnormalities present from birth. Here are some of the most common types:

- Septal Defects: A hole in the wall separating the heart’s chambers, commonly referred to as a “hole in the heart.” It can occur between the atria (upper chambers) or the ventricles (lower chambers).

- Coarctation of the Aorta: A narrowing of the aorta, the main artery responsible for carrying blood from the heart to the rest of the body, leading to restricted blood flow.

- Tetralogy of Fallot: A complex defect involving four heart abnormalities that impact blood circulation and cause a bluish skin discoloration (cyanosis).

- Pulmonary Valve Stenosis: A condition where the pulmonary valve, controlling blood flow from the right ventricle to the lungs, is abnormally narrow, making it difficult for blood to pass efficiently.

- Transposition of the Great Arteries (TGA): A condition where the positioning of major arteries and valves is reversed. The aorta connects to the right ventricle instead of the left, while the pulmonary artery connects to the left ventricle instead of the right, leading to poor oxygen circulation in the body.

- Underdeveloped Heart: Occurs when part of the heart does not form correctly or remains underdeveloped, affecting its ability to pump blood effectively. One example is Hypoplastic Left Heart Syndrome.

Heart hole (the opening between the ventricles or atria)

Congenital heart defects in children can include abnormalities like Atrial Septal Defect (ASD), a condition where a hole forms in the atrial septum, the wall separating the heart’s two upper chambers (atria). ASD is a common congenital heart defect that results from improper septum development, often referred to as a “hole in the heart.” This defect disrupts normal blood flow, causing some oxygen-rich blood to move from the left atrium into the right atrium instead of circulating through the body. As a result, the right atrium receives excess oxygenated blood,

which is then sent back to the lungs.

Another type of congenital heart defect is Ventricular Septal Defect (VSD), a hole between the two lower chambers of the heart (right and left ventricles) that exists from birth. This condition redirects oxygen-rich blood back into the lungs instead of allowing it to be pumped throughout the body.

A ventricular septal defect alters blood circulation, causing oxygenated blood to mix with oxygen-poor blood, increasing lung pressure, and forcing the heart to work harder. While minor ventricular septal defects may not cause noticeable health issues, moderate to severe cases may require surgical intervention to prevent complications.

Aortic valve stenosis and pulmonary valve stenosis

Congenital heart defects in children include conditions like aortic valve stenosis, a common defect that disrupts normal blood flow in the body. Parents may notice signs such as their child getting tired easily while playing or experiencing difficulty breathing, which could indicate a narrowed heart valve.

This narrowing can occur in the aortic valve or at the beginning of the aorta, the major artery responsible for delivering oxygen-rich blood from the heart to the body. As the heart struggles to pump blood efficiently, this added strain may weaken the heart muscle over time.

Similarly, pulmonary valve stenosis affects the valve that directs blood from the heart to the lungs. A narrowed pulmonary valve restricts the amount of oxygenated blood reaching the lungs, potentially impacting a child’s breathing and activity levels. The severity of these conditions varies, with symptoms including fatigue, breathing difficulties, cyanosis, or poor growth.

Doctors commonly use an echocardiogram to obtain a detailed view of the valve and diagnose the defect accurately. Treatment depends on the degree of stenosis and may involve monitoring, catheterization to widen the artery, or surgery in more severe cases. Early intervention is crucial for improving heart function and reducing long-term complications.

What are the symptoms of congenital heart defects in children?

Symptoms of congenital heart defects in children can vary due to the wide range of heart abnormalities. Common signs of congenital heart disease include:

- Cyanosis, pale or bluish discoloration of the lips, tongue, or nails, which may be more or less noticeable depending on skin tone

- Rapid breathing

- Accelerated heartbeat

- Swelling in the legs, abdomen, or around the eyes

- Shortness of breath during feeding in infants, making weight gain difficult, or during physical activity in older children and adults

- Extreme fatigue with minimal exertion

- Fainting during physical activity

How are congenital heart defects diagnosed in children?

Before birth, doctors can detect congenital heart defects in children using ultrasound imaging of the fetal heart. This specialized test, known as a fetal echocardiogram, is typically conducted between the 18th and 22nd weeks of pregnancy to identify potential heart abnormalities. All newborns undergo routine screening for congenital heart defects in the first few days after birth.

A pulse oximeter on the baby’s hand or foot measures oxygen levels in the blood. If oxygen levels are lower than expected, further testing is performed to confirm the presence of a congenital heart defect.

Doctors use a combination of approaches to diagnose congenital heart defects in children or adults. A clinical examination helps detect abnormal heart sounds, while heart-specific tests such as echocardiograms, electrocardiograms (ECG), chest X-rays, and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) provide detailed assessments of the heart’s structure and function. In some cases, genetic testing may be conducted to identify inherited conditions that might contribute to developing congenital heart defects.

Cyanosis in infants as an early risk indicator

Congenital heart defects in children can lead to cyanotic episodes, commonly referred to as blue spells. These episodes occur when inadequate blood reaches the baby’s lungs, resulting in low oxygen levels in the bloodstream. These episodes are considered medical emergencies and require immediate attention. During a cyanotic event, a child may exhibit signs of distress, including sudden discomfort, irritability, decreased alertness, rapid and deep breathing, and bluish skin discoloration, particularly around the mouth and face.

When an infant experiences a cyanotic episode, place the baby on its back and gently bend its legs until its knees touch its chest. Provide reassurance while closely monitoring its breathing and skin color. For older children, position them on their side with their legs tucked into their chest, encouraging slow and deep breathing. If the episode lasts longer than a minute or if the child becomes unresponsive, unconscious, or faints, seek immediate emergency medical assistance.

Echocardiography and magnetic resonance imaging

One of the most significant advancements in the care of children with congenital heart defects is the ability to diagnose complex conditions without requiring surgery. Initially, two-dimensional echocardiography provided detailed imaging of the heart’s anatomy. Later, Doppler technology was introduced, allowing for precise blood pressure and flow measurements. Combining these techniques has significantly reduced the need for cardiac catheterization in diagnosing most pediatric heart conditions. Echocardiography is also routinely used in cardiac imaging during surgeries and pregnancy.

Additionally, three-dimensional Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) has enhanced diagnostic capabilities by accurately measuring the size of irregularly shaped heart chambers, such as the right ventricle, and assessing blood flow irregularities, including valve leakage. As digital technology advances, future developments will further simplify diagnosing and treating congenital heart defects in children, reducing the need for invasive procedures.

How to treat congenital heart defects in children

Treatment for congenital heart defects in children depends on the type and severity of the condition. Some cases require cardiac catheterization to repair minor defects, such as a small hole in the heart’s inner wall. Medications may be prescribed for specific congenital heart defects, including patent ductus arteriosus, to help manage symptoms and improve heart function. Since congenital heart disease often necessitates lifelong care, affected individuals require specialized follow-up throughout childhood and adulthood, as complex heart conditions can lead to additional complications, such as arrhythmias or valve disease over time.

While surgical and interventional procedures help manage congenital heart defects, they do not always serve as a definitive cure. Physical activity may be restricted, and additional precautions may be necessary to prevent infections. In some cases, individuals need multiple surgeries or catheterizations throughout their lives, along with medications to support heart function and overall well-being.

Surgery versus cardiac catheterization in the management of congenital heart defects in children

Surgical procedures and catheter-based treatments are commonly used to manage severe cases of congenital heart defects in children. Cardiac catheterization offers a minimally invasive approach for correcting certain pediatric congenital heart defects using thin, flexible tubes known as catheters. This method enables doctors to treat heart abnormalities without requiring open-heart surgery.

The procedure involves inserting a catheter through a blood vessel and guiding it to the heart, where specialized instruments are passed through it to perform the necessary repairs. For instance, the doctor may close holes in the heart or widen narrowed areas to restore proper blood flow.

For more complex congenital heart defects, heart surgery may be required. Depending on the severity of the condition, a child may undergo open-heart surgery or minimally invasive heart surgery to address the defect. The specific surgical approach is determined by the nature of the heart defect and the patient’s needs.

The role of follow-up and rehabilitation after treatment of congenital heart defects in children

Follow-up and rehabilitation are crucial after treating congenital heart defects in children, whether through surgery or catheterization. After a successful procedure, ongoing monitoring by a specialized cardiologist is still essential to assess heart function and detect potential complications such as arrhythmias or valve leakage. Regular follow-ups typically include diagnostic tests such as ECGs and echocardiograms to ensure the heart continues to function effectively.

Rehabilitation focuses on providing physical and emotional support to the child through structured activity programs, nutritional guidance, and psychosocial interventions. These efforts help the child adjust and regain their daily life. Light to moderate participation in sports under medical supervision is often encouraged, as it helps improve physical fitness and self-confidence. Continuous follow-up and rehabilitation play a key role in maintaining stability and ensuring the child’s best possible quality of life.

The importance of long-term cardiac follow-up for children with congenital heart defects

Long-term follow-up is crucial in managing congenital heart defects in children, ensuring proper nutrition and overall well-being. Some children with heart defects may experience slower growth, appearing smaller or thinner than their peers. Feeding difficulties can lead to inadequate weight gain, while an overworked heart may cause them to burn more calories than usual. After treatment, many children show improvements in both growth and weight gain. Additionally, congenital heart defects can be linked to oral health issues, including tooth decay, gum bleeding, and cavities.

Proper dental care is essential in preventing complications. Physical activity also benefits heart health, So parents and caregivers should consult healthcare providers to determine which exercises are safe and suitable for children with these heart defects.

Congenital heart defects in children can be concerning at first, but with early diagnosis and advancements in medical treatment, they can be effectively managed. Understanding the nature of the condition, identifying early signs and symptoms, and ensuring regular cardiac follow-ups play a vital role in supporting a child’s healthy growth and development. Access to specialized cardiac care and consistent evaluation significantly improves the chances of leading a stable and healthy life. If you notice any unusual signs, consulting a pediatric cardiologist promptly is recommended, as early detection is the key to successful treatment and a brighter future.

Sources:

- Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia. (n.d.). Congenital heart disease

- NHS. (n.d.). Treatment. In Congenital heart disease

- MedlinePlus. (n.d.). Congenital Heart Defects. U.S. National Library of Medicine